The story of the Institute for Gravitronomic Inertiametrics begins humbly, with a father, a daughter, and a need for better ointments.

In early spring of 1864, Rodolphe Hesketh-Dorleac and his daughter Magda arrived in St. Louis, Missouri, from Ghent, Belgium, having traversed the Atlantic with a single trunk, an armful of diplomas, and a small portable alembic. They brought with them generations of scientific tradition, a profound belief in self-derived knowledge, and a near-religious trust in the curative properties of almost everything.

Rodolphe’s own father, Frédéric-Étienne Hesketh-Dorleac, was the first in the family line to identify the therapeutic applications of lemon vapor and igneous loam. His brother Jean-Luc once brewed a tea so stabilizing it was ruled “emotionally neutral” by the Belgian government.

Rodolphe was a kind man, as recalled by his daughter and apprentices. He made a habit of injecting shop employees with restoratives, cure-alls, and distilled emotions free of charge, whether they wanted it or not. He donated regularly to local causes, such as the Women’s Suffrage League, the Society for the Promotion of Irony, the Fraternal Organization of Identical Twins, the Gateway City Mutual Railroad Bonds Children’s Theatre, and the local zoo.

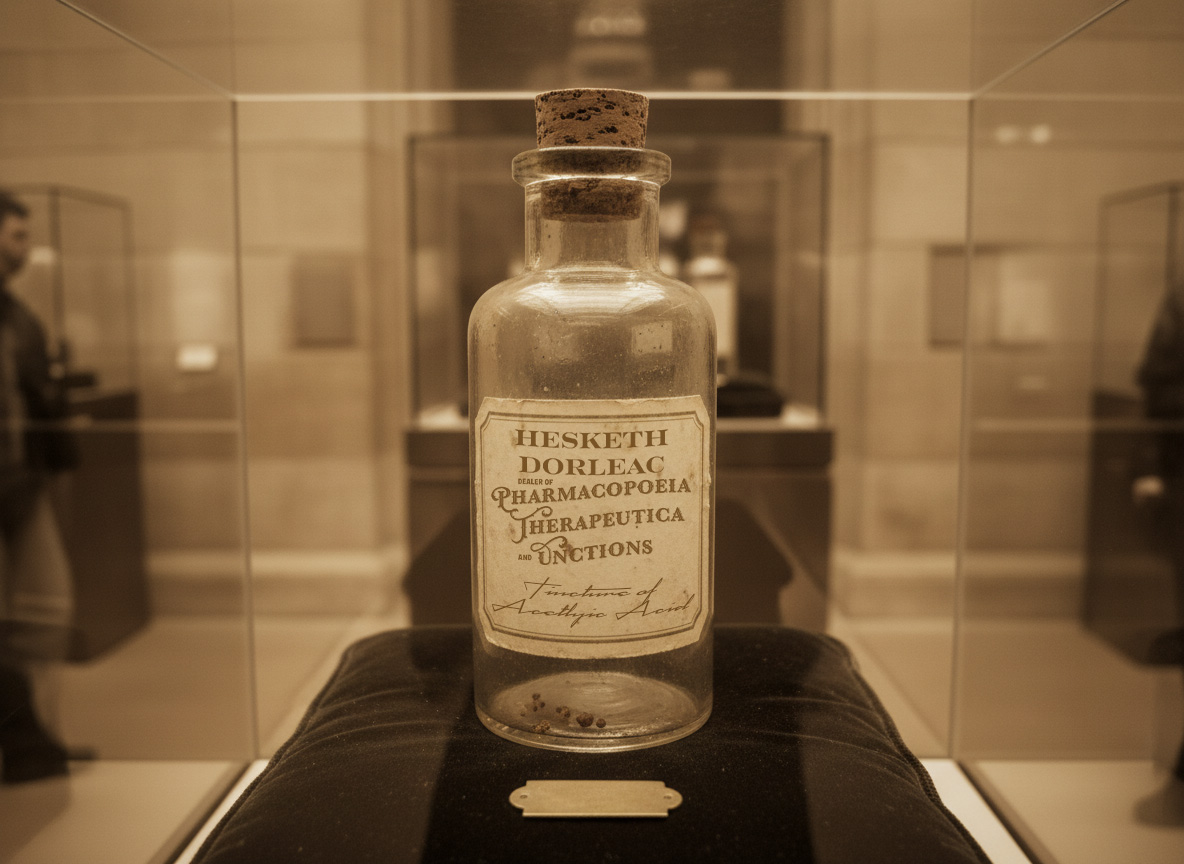

The new shop, The House of Thirteen Essences, was opened in a corner storefront on the edge of the St. Louis Exposition Grounds. The father/daughter team advertised themselves as purveyors of pharmacopoeia, therapeutica, and unctions. The shop quickly developed a small but devoted clientele, drawn by promises of vital elongation and humoral homeostasis. Tinctures developed during these years are kept secret in the Institute’s Bureau of Applied Salves.

Products included:

- Serum Vivace – a periwinkle tonic for “general uprightness and refusal to quit”

- Celandine Bolus – for sore joints, faded memories, or pettiness

- Phlogiston Reversible – sold strictly as a curiosity and for parties

- Verdigris Dispensation – for the addition or removal of miasmas, depending on dosage

- The Third Tincture – unclear in effect, but frequently reordered

Rodolphe’s extensive journals, now on display in the Institute’s public archives, include the prescient entry:

We are not healers. We are restorers of spirit and purpose; we are students of celestial mechanics; we are dreamweavers; we are midwives of thought and succeeders to the praxis of reality.

Interpretation of the elder Hesketh-Dorleac’s journals is ongoing in the Department of Literary Criticism and Hagiography.

Magda herself was already a successful theoretician in the fields of abstract anatomy and differential sublimation. The first in the family to hold six post-graduate degrees, Magda generously applied her knowledge to the woes and ailments of the people of St. Louis. One patron later remarked to a local newspaper that his visit made him “feel so good I could fly!” It is not clear if he achieved flight, though it cannot be ruled out.

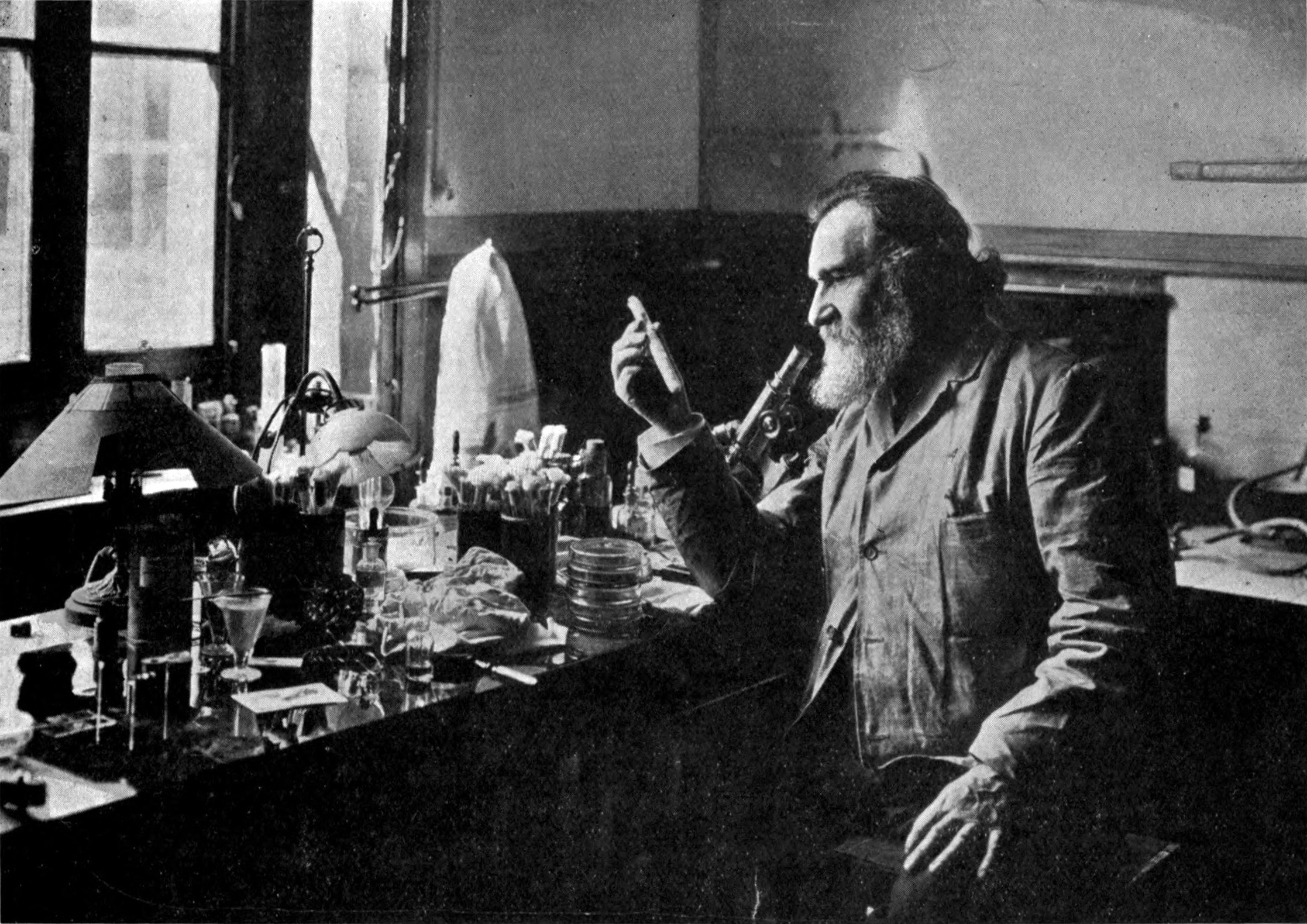

After business hours, the Hesketh-Dorleacs conducted experiments in the drug store’s basement. Their work yielded small-scale discoveries of scientific note, including:

- The first documented instance of viscous smoke

- A successful attempt to shock milk into plasma

- A formula that rendered bread reflective (i.e. mirror-like, not thoughtful, though that was on Magda’s wish list for some time)

- The synthesis of a liquid with no surface tension and very little interest in remaining in containers.

Rodolphe himself lived to the age of 103, finally succumbing in 1894 during a quiet moment in his study, mid-sentence.

“I am nearly—”

—Final words, according to Magda

His passing left Magda, age 58, the sole inheritor of the family’s full scientific corpus: 765 ledgers, 6,000 sealed jars, dozens of dirty beakers, and one small wooden box marked To Be Understood.

It is from these origins, equal parts apothecary, laboratory, and metaphysical dare, that Dr. Prof. Magda Hesketh-Dorleac would rise to become the founding mind behind the Institute for Gravitronomic Inertiametrics in 1901, and the world’s first officially recognized scientician.

Marcus Thornwood, Director of Communications for the Institute

Reproduced from On the History and Development of Scienceonomy (1927) by Dr. Stu D’Apples